Housing, labor, and the passage of time: an interview with Whitney Sanford

HK: "How do you decide what goes into your compositions?"

WS: "Composition and subject matter are two different things. With this body, the subject determines the composition.

A year ago, I was in Crestet, France, a tiny medieval, hilltop town with a population of 35. The buildings were identical in style and palette, but upon closer scrutiny, I saw that all of the buildings were crafted from hand-holdable stones. Surveying the countryside I noticed that there wasn’t a quarry or a stone mountain around. This may sound silly but it was one of the most humanizing moments in my life. This population needed housing to the degree of carting pebbles from miles around.

Living in San Francisco, we have massive economic disparity and the need for housing is at an all-time high. I’ve watched tenement camps develop, migrate, disintegrate in the weather, or be evacuated by local politicians. For me, the dehumanization felt from being homeless is horrific. The impetus of this project: housing is a requirement for all. The question is: what are the similarities in our quest for our most fundamental need, and then what is it that keeps us separate and at odds?

In terms of my method, I travel as much as I can, but when I can’t- I utilize resources from the internet. By using anonymous drone photographs, I can explore the various decision-making processes around the world in order to better understand our humanism. The irony is not lost on me. By using the means of surveillance to explore our most culturally intimate element feels both confused and powerless. This powerlessness goes into the composition, as in I did not take these photographs. I did not lay these stones or paint these houses. As an example, when I was in Ravenna, in the baptistry, touching the spot where the priest’s hand sat for centuries, feeling its sag, the fingertips embedded in the marble, I became addicted with the desire to know how things have come to be and what has transpired."

HK: "One of my favorite things about your work, especially your most recent series of different cities around the world, is that at first glance it seems like an entirely representational image. When I look more closely, I see that there are special details that seem to have come from a train of thought or a profound idea instead of a literal object that exists in reality. How do you come up with these added elements?"

WS: "You are asking me for all of my secrets!

Previously, I played with cultural symbolism and mythology, overlapping different media that felt relevant. With this project, I wanted to simplify the subject matter. That said: art is both object and artifice. I aim for representational but then things change. Through the art-making process, life happens, paint dries, the air quality shifts, the sun sets, your dog gets needy. To be honest, these pieces create an internal battle, and yet I remain as exploratory as ever.

I also include more personal additions; what I love about these explorations is finding things like a pair of underwear hung outside a window, or a cat on a windowsill. Even better are the cracks in walls where old crests have been removed or piazzas where old monuments have fallen.

As for the more ambiguous elements: art is living. Through the process, maybe I doodle, or fudge things; my hand gets lazy and smudges things sometimes, but the beauty of art making for me is the subconscious stuff. My favorite part is that after the whole battle I can take a seat back and look at it. Everytime I discover something new about me. It’s a dialogue in exploring the unknown."

HK: "How much planning goes into each piece? Do you spend more time sketching or painting?"

WS: "Currently, I have about fifty pieces I would like to complete by June. When I start a piece, I sit down with all the imagery collected, pick the one that resonates at the moment, and then begin the drawing process. I’m torn between working with images of cities that are at risk of climate change and sites of never-ending religious wars. Also, I like pretty places. Whatever image I choose, the drawing process usually requires a few weeks. “Obsessive” is to put it gently.

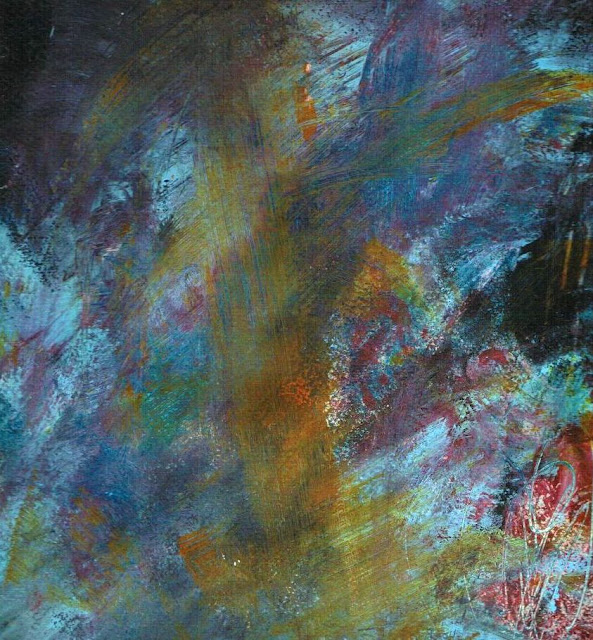

Considering myself more of a painter than an illustrator, I’d think that when it comes time for the color application I would be to the moon, but my most comfortable media is oil which tends to be saturated vs the slightly ephemeral element of these watercolors. I find myself holding my breath a lot. And then there’s precision. Pen and ruler is one thing; stick and hair, another, but:

Let’s talk media for second. For this project, I have chosen watercolor specifically because of its impermanence. Yes, oils would lend heft and vibrancy. I do use acrylic to get specific colors to pop; gouache-sometimes, but watercolor is fallibility. It speaks to the honesty of the human endeavor and the inability to control/maintain everything we attempt."

HK: "Your color palettes are very mood-evoking. Do you use color to exaggerate the human experience of each palate (to evoke emotion), or is the color more true to reality/the architecture it represents? Is it a balance of both?"

WS: "I’ve worked as a figure painter for the majority of my adult life and because of that, I treat these as portraits of the cities. I am limited to the colors I have access to, but the tone and tenor of the place in question is what hypnotizes me. For example, the paintings I have done of China require fluorescent paint to depict a more neon culture; Yemen requires stone tones. There are times when I break the rules a little. I think alizarin crimson should be in everything."

HK: "Art, often times, encompasses a spectrum of deadpan representations to the entirely abstract. Sometimes it can be both deadpan and abstract, depending on what the artist is trying to show (i.e. the object, an emotion, the viewer themselves). Is there anything in this series (The Way We Live) that you are trying to show in deadpan? What have your viewers said they've seen?"

WS: "I like this question because I don’t think most people that view my work know what to make of it. Going back to Crestet, humans need housing. As a species, we are community-oriented. Historically speaking, we either inhabit, flee or dominate places and nothing more than housing indicates that. Civilians are caught between political/economic rivalry; revolutions occur, resources end, dominance happens. What resonates with me is again the idea of stones carried, patterns carved, silent elements of resistance put into/removed from stone. My question with this project is that as we grow more globally conscious, why are we becoming more divisive? Aren’t we all in this together?

To answer, I intend to present these as deadpan. I’m not here to soap-box or judge, but I don’t want people to be remiss in the world to the struggles/existences of “everyone”. Though I may not know you or ever get to see your home, I recognize and celebrate the ways these homes have been created. And of course, using found imagery, I’m not in control of the composition, lending these pieces to a type of abstraction and hopefully personal interaction. Again, art is alive and a dialogue."

See Whitney Sanford's artwork from "The Way We Live" here.

Comments

Post a Comment